—Your presentation is like this: “I write. This is a declaration of principles in these times”. You also wrote: “How the threads look to publishers who profit from authors who sell well. Behind the scenes they make fun of them and even despise their writing, publicly praising them in the sashes." Is it different to be an author than an author?

—For literature, no. This is not a radical or philosophical difference. It is not a difference in terms of art, if you want to think of a definition: what is writing, what is making a work, what is a work, what is music.

"Do they make fun of them or do they make fun of them too?"

—What I meant to say is an annoying, dangerous and difficult subject to approach. At this time, the market prefers women or sexual diversities other than the “heterosexual man” pattern. They think they will sell more with women. There is an inclination in this regard, both from the large multinational mainstream publishers and from the small ones. There is something legitimate in this, but also, as always, there are publishers who fluctuate, take advantage of it, who enjoy it. They want to sell one, two, three or four more books and enter a festival or put on the band of ten editions sold. There are publishers anywhere in the world who off the record or behind the scenes despise that literature that they venerate in their belts. They despise her, but they do business.

“What the right did now the left does.”

—In the book “Symbolic Images”, the art historian Ernst Gombrich tells how there were intellectuals in the courts or patrons of the Renaissance who made a kind of program of what would later become the work of art, painting or fresco. They said which elements of classical mythology or the Bible had to be captured in images. Does any of that still exist?

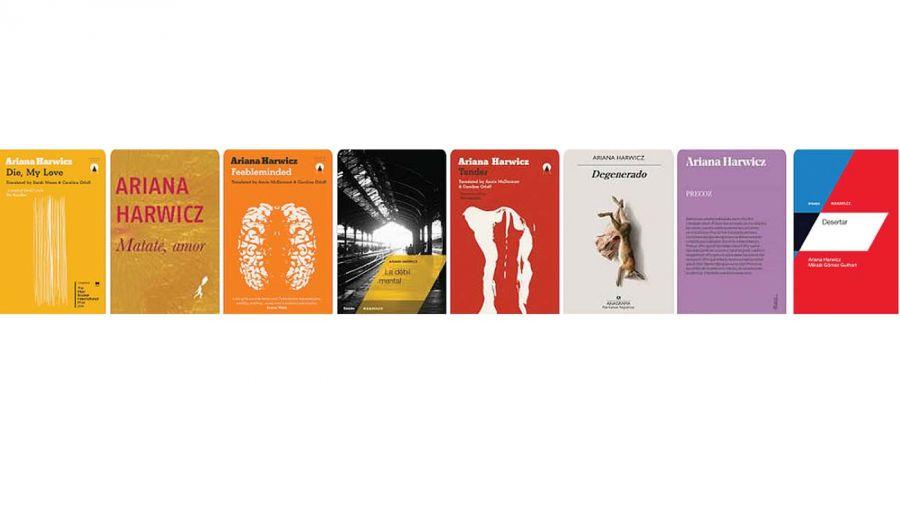

'Thomas Bernhard is one of the greats. Of those writers who vomit truths and who hate the world. He is one of the last great authors of that style. He mocks in a text that I am reading in French of those painters that you mention. He also speaks of the Renaissance. Artists who painted for the court, to order. All his work was governed by commission. He makes fun of them and does not consider them artists, far from it. Art is always linked to power and power to corruption. I'm even ashamed to say it. What varies is the shape. What I can observe in these ten years since Matate amor, from 2012 to 2022, in this decade that I was quite in the Argentine literary field, but also from other countries, that was radicalized. Now it is written almost exclusively for the market. There are always exceptions, there are always artists and there are always dissidents, but the vast majority write to conform to the market. You see it on the first page. Publishers ask for it. Of course one can refuse.

—You faced a situation, you just mentioned “Kill yourself love”, Twitter blocked your account at some point for posting the name of your first novel alleging that it promoted suicide. You cataloged it as "a mechanism of ideological coercion with the guidelines and coordinates of liberalism and capitalism." What is your relationship with networks?

—I wish the Twitter thing had been the only thing. It's not that I'm in hiding and they're torturing me. To affirm it would be almost a mockery. They would rightfully go for the jugular. They would tell me: “You are calm in Paris, in your small apartment, but safe”. It's true. It's not that she's kidnapped. But the methods of ideological intimidation, which perhaps we all suffer from, in my case also existed and still exist. First about Twitter, almost an anecdote, but symptomatic. Not once, not twice, not three. It happens every time I put “Kill yourself love”, or that some reader puts “Kill yourself love”, now I put “kill” or “love me love”. But he suspends my account for 24 or 48 hours and sends me phone numbers to call as Alcoholics Anonymous, but not against suicide, because they say that Kill yourself love is a title that encourages self-harm, that encourages to act and commit suicide and annihilate. At first I was amused, but there is nothing funny about it. Other things happened to me, some I cannot tell. Matate amor was highly questioned, even legally speaking, in France. I mean, I have legal problems with that novel. France, 21st century, not Afghanistan and not 15th century. My relationship with the networks is very tortuous. I don't have 300 thousand followers or a million. I do not have a position taken. I feel like a traitor writing on Twitter because logically it is a company that has an ideology that I despise, but getting out of there and self-suppressing seems to me like inflicting a punishment. You have to accept being in corrupt media.

—In another interview you said: “For an author the greatest challenge is not to give in to the militant mission”. Is it still written against its own ideology?

—In a prologue I wrote for an edition of Anagrama of the three novels that constitute a kind of involuntary trilogy, I say that. It is very obvious, perhaps little said or little said by women. We are led to believe that art must follow an ideological prerogative or must be military in order to have prestige and political power. It's the opposite. Not following a clear ideological line, not drinking from the waters of ideology, there can be a great work. I know of no great work whose foundations are ideological. That all work is political is obvious. The authors I like are those who did not give in to any kind of political or ideological intimidation. For example, Imre Kertész, a survivor of the death camps and the worst dictatorship, does not give in to the temptation of being the example of a survivor of the Shoah or the Holocaust. He does not give in to the temptation to place himself in the range of the victim. He runs from there.

—Is there something in progressivism that is more marked than political correctness and the theory of cancellation? Something more modest, coercive, of the order of the superego.

—In Europe, sure, yes; also in the United States. Each country adopts doxa, progressivism, censorship, in a different way. Argentina is another field. I see it more extreme in Europe than in Latin America. In Europe, Canada and the United States it is progressives who have betrayed themselves. In France, the left raised the flag to the point of giving their lives for absolute transgression and freedom of expression. It is the same left that is absolutely subject to the law of censorship, self-censorship, political correctness, fear. Yes absolutely. What the right did now does the left. It is that clear. At least here in France it is like that. In Argentina it works differently.

—Let's take advantage of your distance, how do you see it? In Argentina a new coordinate of the most rebellious rights is discussed. Something that in the past was awarded to the left.

—I am interested in thinking about my country. The political coordinates of Argentina. I am very united and I try not to make clumsy reductionisms. The right takes the torch, I don't know with what consequences. It is a true halo of transgression and rebellion and of breaking norms and amorality. It is true that before it was exclusive to the left. The resurgence of new more rebellious rights is true that it happens in Argentina.

“Before they called me 'shitty Jew'; now, in the name of political correctness, they call me 'shitty white'.”

—What difference do you find between the politically correct French and the Argentine?

—The dead are different, because here we have Islamism, an anti-Semitism in crescendo. I am not saying that there is no anti-Semitism in Argentina, it is a passion common to the entire world. There is no country that does not have a portion of that anti-Semitic passion. In Argentina it has now been shown that it is still in force, but here there are deaths. Someone told me it was the same. But no: here there are dead. I saw them lying in the street. Here there is an exile of the Jews to Israel. The community was decimated. There is fear. Here they beheaded a Geography and History teacher, Samuel Paty, they beheaded priests in the church, in the street, they kidnapped a journalist the other day. In Argentina it seems to me that political correctness is installed. There is an ambient censorship. Journalists think ten times what to publish, they downloaded newspaper notes, but I don't know if heads roll. It is the only difference. Environmental censorship is installed in Argentina as well, journalists can tell. In case they can.

—A theme that circulates through the books of your “involuntary trilogy” is why the son should grow up, why the mother should grow old before the son, who said that this is a law and all your perplexity about why it was ask someone who wasn't a mother why she wasn't.

"Let's talk motherhood then." I was listening to a poem by Anne Sexton, another one who is an artist for me. We all know her. After giving birth, and that she was a bourgeois from the United States, not someone poor declasse in a third world country, but a privileged 20th century, middle-class bourgeois daughter from the United States, she was in a state of what is called postpartum depression . It's a label. If you suffer now, I don't want to imagine what it was like a century or half a century ago. She is admitted to a neuropsychiatric hospital and what saves her is writing. The psychoanalyst tells her: "You're not crazy, you're a poet." Writing “saves” her. She saves in quotes because she later drinks a cognac, a whiskey and starts the car engine and she commits suicide at 45 years old. I think about her a lot generationally because I'm close to the date she died, at 45. I don't know if I had postpartum depression because I don't like it, I hate being diagnosed since I'm not a doctor, I never went to a psychologist, but I did have a lot of anguish after childbirth, I don't want to pathologize it. That kind of absolute existential anguish led me to write Matate amor, it made me enter literature. The anguish of motherhood opened the doors of literature for me. Not only. Today more than ever motherhood is something political. I thought not, but I realize that it is. I realize here because of the legal problems I am having, because my novel is being judged, because motherhood continues to be a great political issue. The most radical feminists are bothered by motherhood because they see it as a yoke, an alienation. Motherhood is at the center of feminist, anti-Semitic disputes. They don't take our children but almost. Before they took the children of women who wanted to get divorced. Many times now too. A woman wants to get a divorce and is punished by taking her children away.

—You said in another interview that the maternity mandate was greater in Argentina than in other parts of the world.

-In Latin America. Mexicans or Colombians can also say it. When you go to festivals and fairs with your books, it's impressive. Beyond the great differences, that point in common with readers anywhere in Latin America is perceived. In Europe, the demographics of white Judeo-Christian Europeans are plummeting. What happens with immigration is different.

"There are publishers who despise the very literature with which they do business."

"To what do you attribute this change?"

I see a lot of changes. As an immigrant, as a foreigner, I am not French, I see that European women are more distant with motherhood. Motherhood is a philosophical issue, but socially there is a slightly greater distance. You have only one child, at most two, you leave him in daycare from the age of six months. Women don't breastfeed or only do so for a month, two, three. I speak broadly. I see a slightly more distant relationship with another type of freedom than the mandate and the policy on motherhood in Latin America, where the one who does not have children is almost a deformed woman. I don't want to exaggerate, but she is almost an eccentric who doesn't have children. A rare, misshapen, deviant. She forgives her if she has money or has succeeded in something, but she always marks herself: “she didn't have children”. In Europe it is not so.

—In “Matate amor” you begin: “I reclined on the grass between fallen trees and the sun that warms the palm of my hand. She gave me the impression of carrying a knife with which she was going to bleed me out from a cut in the jugular. Behind, in the decoration of a house between decadent and familiar, I could hear the voices of my son and my husband”. Is there something self-referential in this set?

—I love that you ask me such profound questions but with such absolute seriousness. The novel must be lived yes or yes. This and all the others, Degenerate too and is a man accused of sexual assault. I am not a man, nor old nor did I sexually assault any girl. However, novels have to be lived. In this case it is very obvious that there is empathy. Empathy is a very boring word. There is a bond, a very obvious mirror in the experience of my foreign characters and myself. But novels have to be lived yes or yes. Then you have to write them, but it does not mean that everything that is written has happened. Living a novel does not mean that it has happened anecdotally, but it does mean that it has happened in feeling. It is that feeling of the house as a decoration. That's why all my novels are plays. A family home is a set, it is an artifice, there is something false there. In that sense there is a lot of me.

“Journalists and writers have in common the need for independence.”

—Your novels are short. Is the extension, the brevity, a point of contact between the novel and poetry?

-I think so. Poetry is much more than brevity and synthesis and than ellipsis and a certain kind of cut, abbreviated music. A unique music in few characters. But there is inevitably a relationship with poetry. I didn't want it. You are right.

—And at the same time you mentioned that all of them were ultimately like plays and you told about your experience of adapting novels to theater. How was that intertextual experience?

"It is suffering, but unavoidable." Without suffering there is no writing. They are short novels, very short for the canons of literature, they call them nouvelles. For me they are not. But they are very short novels, and yet they are nineteenth-century. It's 500 pages for the theater. A page in cinema is three minutes, but in theater much more, if they are not monologues said in an exaggeratedly fast way. So the first sacrifice, the first cut, as if it were a movie in the editing room, the first cut was made by me. In Precoz I don't know, but in Matate amor and in La weak mental it was like that. The first big cut was cutting those hundred pages of Precoz down to fifteen. It's terrible. And then the director or those who adapt it go down. It is a work of sculpting, like the title of a book by Andrei Tarkovski, Sculpting in time. Sculpt until leaving the unique stone, the heart. It is difficult, if one wants to maintain a narrative line. You have to go to the heart, and all the digression is lost, which is a shame. But in the theater there are other types of digressions. So the first cut is made by me and then by those who adapt it. Or, in the case of Matate amor, Marilú Marini and Érica Rivas.

How to retrieve a lost savings bond? http://beginner-investors.info/?p=5540

— Maurice Young Fri Oct 01 04:01:07 +0000 2010

—I read that you passed them music and photos. There was an analogical language that was added to the written word.

-Yes. I tortured Julieta Díaz during the two years of the pandemic, and so did Érica. Photographs, paintings... I can't imagine how to compose without those elements. It would seem to me that something is missing if not. He lacks the "piano", and the piano for me gives everything. Afterwards, I don't know how much of that they use. But the text is understood differently when you have the piano score and the painting.

—Let me ask you and come back to feminism. I want to read you a sentence, you said: “It is undeniable that there is something like a revolution underway. You see it in high schools, in how 12, 13, 14 year old girls think. In the rooms of Argentine adolescents there is not only Ricky Martin or the Robbie Williams on duty, but there is also the green scarf, but for there to be a cultural change that modifies a culture rooted in sexist violence, we have to wait.

"Did I say all that you read?" There is always distance. It is the foreigner that one is. I am critical of feminism when feminism is infiltrated, which is the case in Europe. It is different in Argentina. I mean infiltrated by political movements that gangrene, rot and co-opt. I'm not going to explain it to people in politics and journalism like you. Any political man knows it. Apart from those leaks, if I had a female daughter, and even retrospectively the adolescent I was when I was 14, 13, 15 who was active in the slums of Greater Buenos Aires, I can only be happy that they have the green scarf and have a political conscience, despite these captures and these infiltrations. I can't help but get excited about it. I was born in 1977 and lived another time without that awareness. A friend who writes in a newspaper and who works on women's murder cases told me that there is a strange political phenomenon. There is a lot of awareness and marches. Abortion was achieved. The girls have another iconography. There is not only the cute, sexy boy, but also the green scarf. But, on the other hand, they kill them the same as before or more, according to what she told me. Like when these feminist policies of gender awareness, of abuse, of rape were not there. Impunity remains the same.

- Is there a reaction against this process of women's liberation represented by right-wing populism and the extreme right in general? They are white men who react to the rights of minorities, which from their perspective includes women, LGBT people. They are the ones who talk about feminazis and things like that.

"I wish it were that simple." I am not a political analyst. I have to be careful, but I think power surges and power struggles are more complex. I wish it were Donald Trump against Joe Biden or against Vice President Kamala Harris, or Donald Trump against Barack Obama before, or against Hillary Clinton, who are pro-rights, women's freedom, feminism and respect for gender diversity. Lobbies are more complex, because the LGBT lobby also has a lot of power in the United States and also enters areas of totalitarianism.

“I do not know of any great work whose foundations are ideological.”

—How is feminism used politically in France?

—There are demonstrations attended by many people, most of them women. I didn't go to the last one, but I usually go to the demonstrations. Since I am 15 years old I go to the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo. She was very young when José Luis Cabezas was killed. I was always against the pardon, against Carlos Menem, as if to give an example. I have a tradition of going to marches and military. It is not a lack of political awareness. I did not go to that march because I do not agree with that infiltrated feminism, co-opted by power. We march against conjugal violence, how can we not be in favor, but they go to areas where they burn women alive or do not let them leave their houses or torture them, kill them, burn them alive in front of their children for wanting to remove a handkerchief or for nightlife. Or they won't let them into a bar. And they don't go to those territories that are here ten minutes from Paris. You don't have to go to Afghanistan. They don't go to those territories. It's a shame. They don't take risks. You have to confront the white man if he is a rapist, gropes, if there is marital violence. But he is not just the white man.

—The activist Mayra Arena, who was born in a village, has been warning about the fracture of Kirchnerism and the vulnerable sectors. She says that the focus of the ruling party's gender agenda reveals a spirit that is more middle class than linked to the poor. Is there a feminism of the middle class and another of the classes with fewer resources?

“I see it everywhere. There is a kind of ideological trap. There is always the risk of failure. There is always a bit of failure. A feminism that remained as in a fringe. In the United States and here in France as well. It stayed in a fringe of doing justice with the structural violence towards women of a certain middle or upper class. I was born in 1977 in Buenos Aires, and I know what I'm talking about. I had those episodes without coming to rape. I know perfectly well what it is to be harassed or groped. I know about that risk you talk about, but it's true. Yes, it seems that he remained as in a middle class and even the speech remained in a certain middle class. What I was telling you, they continue to kill them the same way in the Conurbano, with the same impunity as before. That's where feminism should come too.

—How is the Parisian Conurbation?

—I feel a bit like in Buenos Aires. It is a horror what I am going to say, but we must not kill the messenger. You pass the Parisian General Paz and go to some poor, Islamized outskirts, where the police, like in Argentina in the slums, are not encouraged to enter, and if they do enter they are fixed. It's no man's land. Doesn't look like France. There are no more French wineries because you can't drink alcohol, meat is halal, women are covered. It is like another country within the country. That is in some peripheries, not in others. Not in those where the rich are, the footballers. In Argentina or Buenos Aires you have to travel an hour by car to reach them. Here, in 15 or 20 minutes, it's another country, other laws. You don't recognize anything in the landscape.

—You wrote on Twitter: “The literature fair in Helsinki began quietly. Before they called me a shitty Jew, now a privileged white, I said to introduce myself. Luckily, no one in the audience asked me about my sexual orientation.” What is expected of women writers today at the political level?

—I was in Helsinki invited by the Argentine ambassador Sergio Baur. I go quite a lot. It moves me particularly, perhaps because I miss Argentina so much. I am quite moved by the relationship with diplomats.

—With something that has to do with Argentina.

—I work a lot with the Embassy of Israel, Serbia, Finland and many others. But as for your question, I don't fully understand that instead of talking about literature, you lecture against racism before an audience. I think Alejandro Dolina said it: it makes no sense to evangelize the evangelized. I spent an hour listening to a speech against racism and against Mexico's endemic violence against women. I felt that they were trying to educate me, as if I were a student. But I already know; and I agree. The risk consists in talking with those who do not think the same. There is something very masturbatory about congratulating each other on not being racist among people who are not racist. No one has a racist or class notion at a book fair. They are poets and writers. So there is a replacement, supplanting the literary debate: it's not that it's apolitical, it's stupid, but literary reflection is replaced by a kind of very poor indoctrination. So if before they called me a shitty Jew and now they call me a shitty white.

—Can you imagine returning to Argentina and being a foreigner forever?

-What question! It's obvious, but I've lived here for 15 years. There is no linearity, there is no integration and assimilation. There is break. Migrations, everyone's and much more if you write. If you write you are outside the dimension of ordinary life. You want to get out of your own life, see yourself from the outside, cut yourself off. But much more if you are a foreigner. Then yes. It's getting harder and harder for me. At the same time it seems to me, I don't know why, impossible to imagine myself writing in Buenos Aires. Maybe it's pure neurosis. Although it is very painful, I like the relationship of living in Europe because of being able to be in Georgia or in Serbia, or in Tel Aviv, or wherever. My grandparents come from Poland, from Romania. So there is also something about going back to a certain origin.

—Speaking of genealogy, Ariana is a name that appears continuously in classical art. The famous painting by Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, "Ariadne's Lament" in Monteverdi's opera, but also in Nietzsche's poem. Do the names mark?

—Oh, what a nice question and how nice it would be to ask them why they chose him. I don't think it has anything to do with any of that. Interestingly, it is also an Italian name, but French. So here they rename me Arianne, although I don't like it. Changing the music of your own name is changing your face. Harwicz doesn't sound the same either. They say it like in Poland. I don't know why they chose my name, but it is definitely a brand. Yes, it is later related to writing, it seems to me so, and the surname as well. They tried like so many to make it less Jewish, but failed.

—Ariadne's thread with which she saves Theseus to get out of the labyrinth after murdering the Minotaur, and then she reinterpreted in Roman mythology as the goddess of freedom. Is there something that imposed a certain degree of freedom, a search for freedom as a mandate?

-In the past? Don't talk to me like she's dead. It is difficult to talk about such solemn topics, but yes: freedom and justice. I always tried to seek justice. In these movements, in these groups in which he participated. She wasn't exactly a militant, she was and was part of movements in which we went to rural schools, from the interior, to Villa Soldati, under the bridge, to the villas. Before Ni Una Menos, much before, and Me Too and all this resurgence of these movements as the predominant ideology. Much earlier, when a beaten woman was like a taboo. But then I got into writing and somehow I try to do justice by writing novels. It does not mean that they are novels, as we said before, that they submit and lower their heads, that they kneel before an ideology. Rather the complete opposite. I can do a little justice by writing these novels, although the operation of art is different from militancy. But they do seek emancipation and justice. It is the most difficult. Perhaps one day I will write from there and another configuration from abroad, from abroad, will be put together.

“It is very tiring to be a foreigner; but it is an essential condition for my writing”

—There is a kind of re-greening of the topic of leaving Argentina and the discussion about leaving or staying. And I wanted to ask you first on your own homework. How is that relationship between writing and being outside?

"It's a subject to talk about at length." To get to write is a sine qua non condition, the first and only philosophical condition and the most important, foreignness. Become what you are. I didn't think it would be like this, it wasn't programmatic. I left Buenos Aires on August 14, 2007. It wasn't in 2001, not fleeing from De la Rúa's helicopter; I am not exiled from the dictatorship, nor persecuted. I left without thinking that I would be able to write and become a writer. I wanted to live in another language. That experience, the most radical of my life, of having another language, of thinking with another language. That causes me a foreignness with the French and by rebound it causes me a foreignness with the Argentinian Spanish from Buenos Aires. Yes, it is a sine qua non condition. How do I put together a sentence, how do I get to put together a language, if I don't have this strange relationship with language? It has nothing to do with the landscape, the Eiffel Tower, seeking economic comfort. Quite the contrary. Here one is much more alone. It's not crying either, but that's how it is. One is more helpless in front of the law and the other. I don't remember which writer said that it was very tiring to be a foreigner: until the end of your days you are the foreigner and the one with the accent. The one who is asked where you come from, where you are from. It's very exhausting. It's like facing yourself all the time. That suffering and that estrangement is given to me by writing. I don't know what it would be like to write in Argentina.

—But do you think and write differently in French than in Spanish? That idea that there are languages, Italian for opera, German for philosophy.

Yes, I am a fake. I did not cross the pond of languages, I did not do what Samuel Beckett, Vladimir Nabokov, Joseph Conrad, José Donoso did. What Fabio Moretti and Morabito did. Like Copi or Witold Gombrowicz. I did not do that Gombrowiczian experiment of merging Spanish and French. I keep writing in Spanish, but translating it in my mind from French. If an important French word comes up for what I want to say, I put it in French and then translate it into Spanish. This effect of translating causes a writing that is already a translation. My novels are already translations.

“The great fear is social death, social exile, symbolic Siberia”

—Is there a common ethic for artistic work and what it has to do with journalistic work regarding becoming independent and taking distance from your own ideology?

-Absolutely. Now when I see a journalist emancipated or with a certain freedom, or separated from the lobby in which he has to operate, right or left, Peronist or anti-Peronist in the case of Argentina, it is almost like a miracle. That emancipation or independence that was previously had should be the same, although with different rules, for the journalist, for the artist, for the writer, for the philosopher.

—Is the big other the audience? Finally, what you have to become independent of and distance yourself from is the audience?

“It's the big change. There are also the bosses that can kick you out. They do. I saw it. Or the publishers who own publishers who stop publishing you, who terminate even signed and paid contracts. I'm not making up what I say. There are all those types of casualties. The great fear is social death, social exile, symbolic Siberia, the symbolic gulag. And that is determined by the networks and by the audience. The audience, the public and the users. There are no readers, there are users. It is the great fear. Many people who are related to power on television, journalists, authors who sell a lot, are very afraid. Men more than women. A little wrong word is equivalent to social death, to exile. Then you don't come back. Many do not return from that exile. Everyone is afraid of being wrong, of the word that makes you skid.

Production: Pablo Helman and Natalia Gelfman.

You may also like

Without mining or Portezuelo, a company that produces wine is born in Malargüe

Goodbye to Carlos Marín: this is the heritage and fortune left by the singer of Il Divo

Study considers that gender equality is not a priority for 70% of global companies

Ceviche to Recoleta and croissants for officials: the bet of the workers of Villa 31 to sell outside the neighborhood